Just five short years ago, hereditary cancer testing was much simpler for patients and healthcare providers. There were finite criteria, associated with a handful of genetic conditions, and healthcare providers could order single-gene (or single-syndrome) genetic testing for patients who met those criteria. Since 2012, the field of genetics has grown, and more healthcare providers are choosing to order multigene panels. There are a variety of panel testing options, and they can range in size considerably. At Ambry Genetics, our panels for hereditary cancer conditions range from 8 genes to 67 genes.

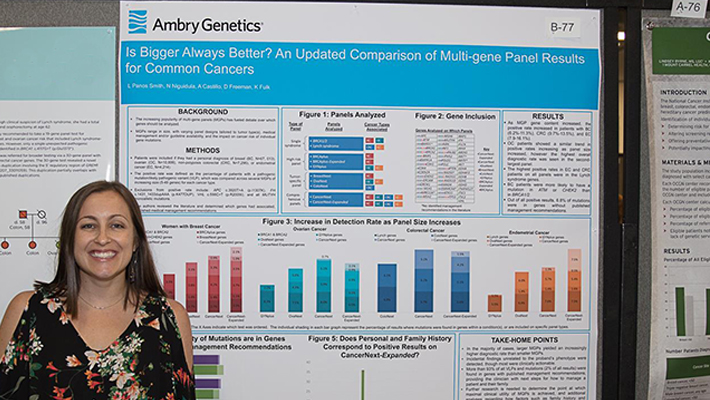

Understandably, healthcare providers are often asking genetic counselors, ”Which panel should I choose?’ and ”Are bigger panels really better for our patients?’ In a recent poster presented at the National Society of Genetic Counselors annual meeting in September 2017, we presented data to help answer these questions.

Our data showed that larger panels usually provide more answers for patients by identifying more disease-causing mutations. Larger panels are able to detect mutations in genes that smaller panels exclude, allowing for a higher diagnostic yield. These mutations were most often in genes that have published management guidelines associated with them, so clinicians can use this information to help guide a patient’s screening and prevention plan.

Additionally, the mutations found on larger panels were often ’unexpected’, or in genes that were not related to the patient’s personal and family history of cancer. For example, an individual with colorectal cancer may learn that they carry a mutation that increases their risk for breast cancer.

Some patients may be pleased to learn of their increased cancer risks and want to explore cancer prevention options. However, other patients may feel frustrated and overwhelmed that they still do not understand the cause of their cancer diagnosis, yet they now have risks for other cancers that they were not expecting.

Prior data (Panos Smith et al., ACMG 2016) showed that variant of unknown significant (VUS) rates also increased as panel size increased. These VUS results are not actionable, and healthcare providers usually use the patient’s personal and family history to determine appropriate management rather than the genetic test result.

By ordering larger cancer panels, we are able to detect more clinically actionable mutations in patients than by using smaller tests, which is beneficial. However, results may be unexpected and there is a higher likelihood of VUS results; therefore, healthcare providers need to have a discussion with patients before testing about the types of results that are possible to ensure that the information will be both helpful and desired.