The adage “knowing is half the battle” describes Trinity Chappelear perfectly. Her dear friend Brandi Preston lost her mother to breast cancer at age 14, spurring Preston to start The Kamie K Preston Hereditary Cancer Foundation, based in Omaha, Nebraska. The non-profit is devoted to educating and supporting awareness for genetic testing to anyone who wants or needs it.

Because of Preston’s actions, after Chappelear’s uncle and cousin were diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, she knew that genetic testing for a hereditary gene mutation could reveal if she had an increased risk of developing pancreatic cancer as well. “Why not have that knowledge?” Chappelear says. “It could save your life.”

During her testing, the technician remarked that she was “a unicorn” when they found out she had a mutation of the ATM gene.

So what is the ATM gene, and what’s a unicorn got to do with this?

The ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) gene lives in our DNA in chromosome 11, which aids in protein development, controls cell growth and repairs damaged DNA.

In Chappelear’s case, being a unicorn means she inherited an ATM gene mutation that can cause breast and pancreatic cancer and other serious diseases without having an immediate family member who was known to have the same genetic mutation.

Living in Nebraska, Chappelear feels lucky to have such close access to the University of Nebraska Medical Center and Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer Center. This state-of-the-art research facility houses the Cancer Prevention & Control Program (CPCP). She describes this center as a “one-stop shop” for genetic testing, counseling, management and care planning.

Finding out that she carries the ATM mutation, Chappelear became more proactive in her health care: increasing mammograms and abdominal scans, watching sugar intake and exercising more to encourage a healthier lifestyle.

“I don’t want to miss out or be a sitting time bomb,” Chappelear says. “If there’s a way to find out earlier, let’s go. I want to be around for my family, my grandkids.”

Chappelear also started talking to her relatives about getting tested. As a result, her daughter has received genetic testing and undergoes routine screening with her health care provider. Chappelear lost her Uncle Dave and cousin Tom to pancreatic cancer not long after she was tested. This sparked conversations about genetic testing amongst her cousins and other family members. So far, only a few cousins have been tested, but she’s working on the rest with friendly reminders.

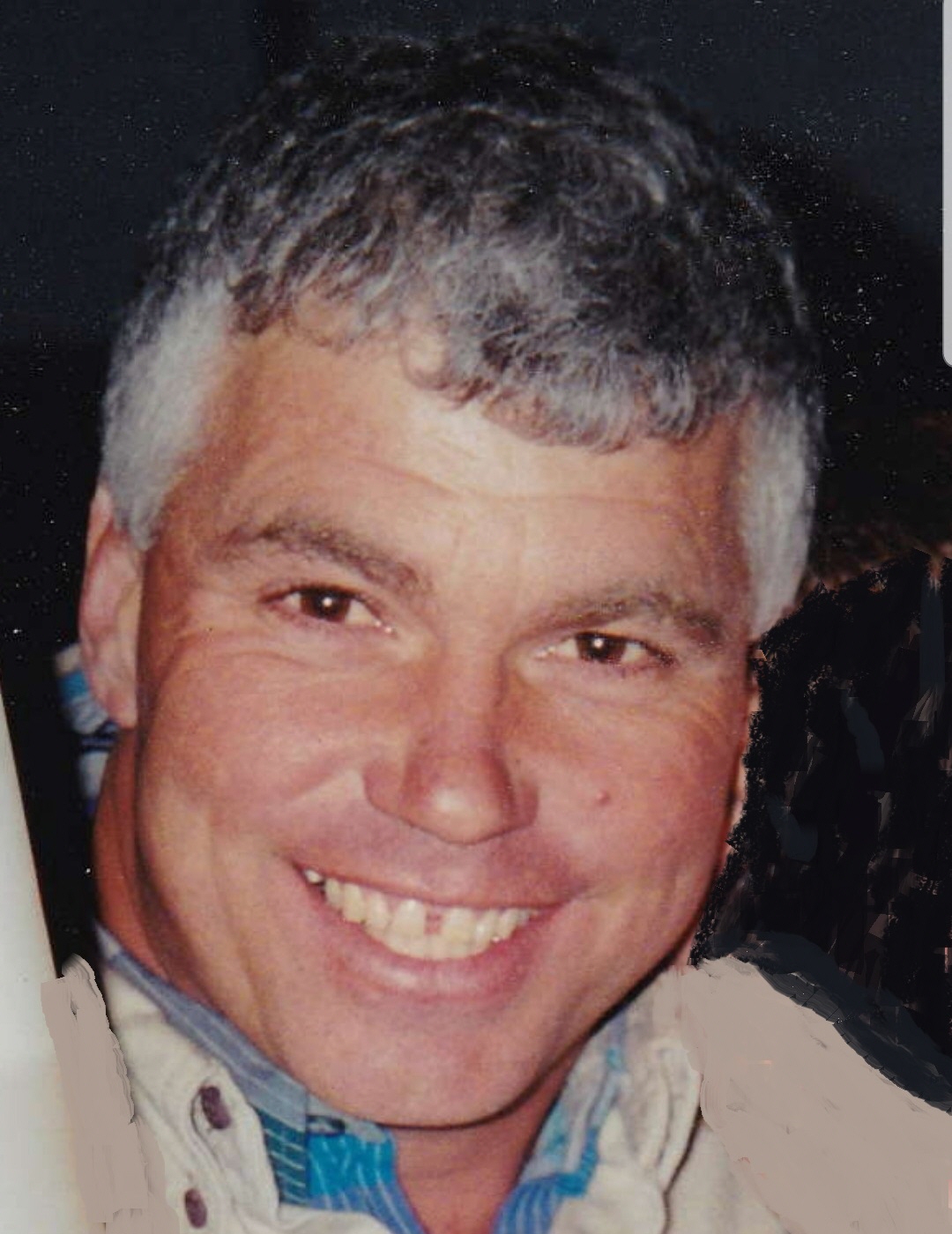

Cousin Tom Johanning.

“My Uncle Dave would have been the first to tell them to get in the truck; you’re going to get tested!” she laughs. “Family was everything to him. He was a trucker, a farmer, and served in the Navy, so his request would have been much more colorful than mine!”

She’s also active in pancreatic cancer studies at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. Recently, Chappelear gave blood to look for a specific marker for pancreatic cancer. If a participant develops pancreatic cancer they’ll go back through their results to see if they can find the same marker in older samples to find a way to catch pancreatic cancer in the early stages through a blood test. The information found in these tests is vital to treating and beating cancer before it starts.

Chappelear’s case is an excellent example of the benefits of assessing genetic risk to develop certain cancers before symptoms appear in order to have appropriate screenings and make proactive life choices. As a result, not only does she enjoy a full, healthy life with her family, but she’s also contributing to a future that includes fewer people facing the same disease that affected her family.

Uncle Dave would approve, with some colorful adjectives included.